I am a huge Chuck Palahniuk fan, and always will be. As a “writer” (compared to him being a Writer), I obsess over his prose, biting narratives and cultural influence.

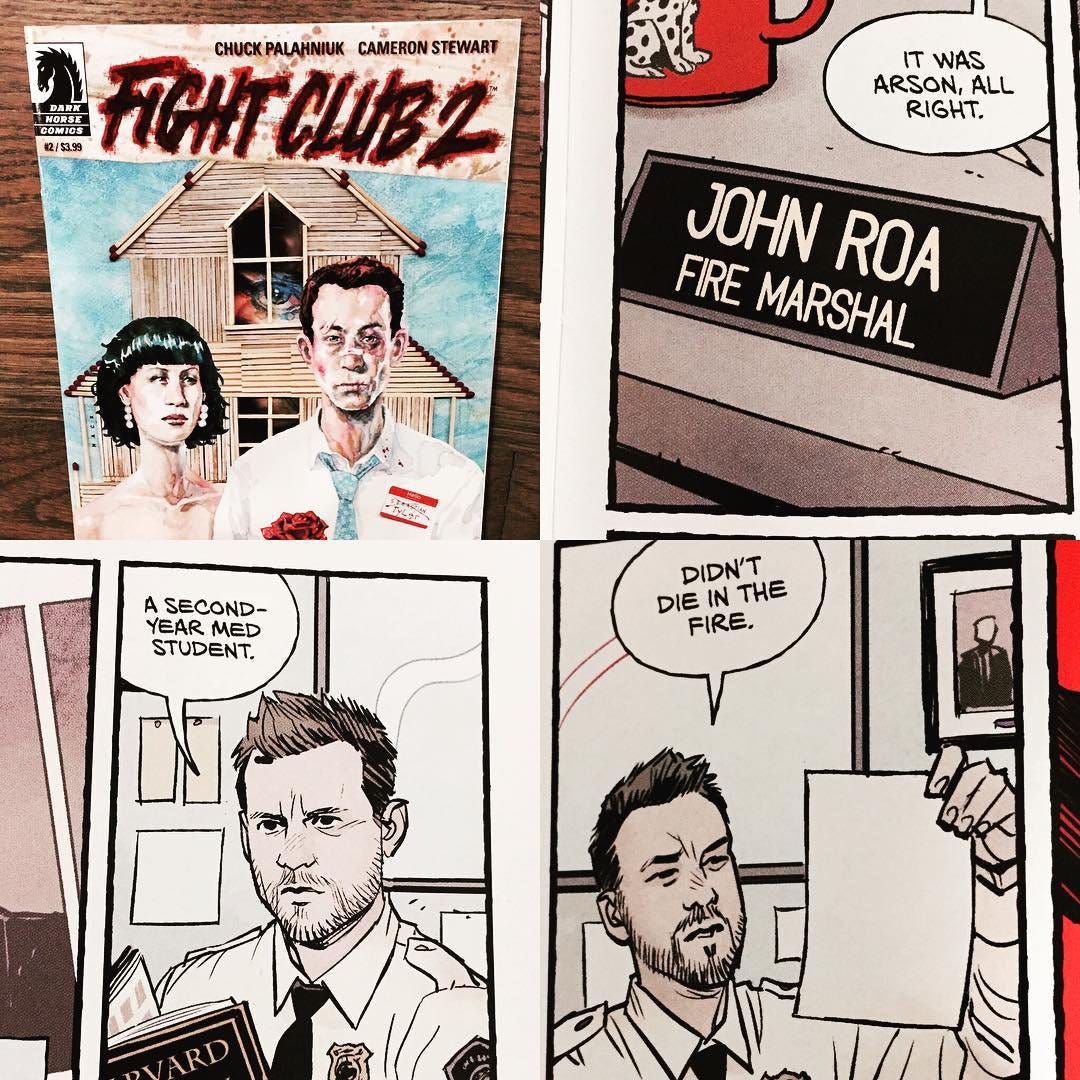

I am one of the lucky ones that has gotten to spend quality time with Palahniuk on several occasions over the years, and there’s an undeniable warmth and quiet wisdom about him—an unexpected contrast to the raging nihilism of his most famous work, Fight Club. He is nicer than his work suggests—significantly so—going so far to make me a character in Fight Club 2. (That’s true. Don’t believe me? Proof below.)

When we talked about Fight Club’s legacy, one point was clear: he never intended to glorify destruction but to diagnose the sickness of disillusioned masculinity. And make no mistake: Fight Club remains a defining work for Gen X men, capturing their frustration at being handed a world where they were told to aspire to greatness only to find that greatness was just another item on the shelf at IKEA.

But here’s the thing: most people haven’t read the book. They know Fight Club as the movie where Brad Pitt, quotable and shredded, builds an army of disillusioned men in dank basements. And while David Fincher’s adaptation is completely brilliant in its own right (even Palahniuk admitted the film’s ending might be better than his original), the novel contains a nuanced depth that films rarely capture. The book dives into the psychology of alienation, the fetishization of violence, and the dark allure of hypermasculinity. “Project Mayhem”, central to the story’s climax, is often remembered as chaos for chaos’ sake—a terrorist cell bent on disrupting the world—but in truth, it’s something deeper. Its members weren’t fighting for material gain—they were fighting to tear down a world they no longer believed had a place for them. It’s an organization built on the premise that when men lose everything, they are finally free to do anything.

And this is where history begins to repeat itself. In 2025, we see the same fury manifesting among young men—only this time, it’s digital, political, and global. The era of chaos, hypermasculinity, incels, and disillusioned youth isn’t a subplot in a novel anymore. It’s the plotline of our reality, except we don't have Fincher screaming "Cut!"

Digital Lost Boys

The idea of Tyler Durden is alive and well today, fermenting in a generation of young men who feel duped.

Today, they’re wandering through the ruins of the American Dream like digital-age lost boys. They were told that a college degree would secure them a job, that hard work would yield prosperity, and that good behavior would be rewarded. But reality hit back. They are working longer hours for less pay, watching housing prices rocket out of reach, and drowning in student debt that makes buying a home feel like a pipe dream. They live in tiny apartments with multiple roommates, trying to make it work on salaries that haven’t budged since 1980. They’re swiping through dating apps where their worth is reduced to a series of photos and a punchy bio, only to be ghosted by women chasing men who seem just a little bit better—richer, hotter, more confident—and statistically, much older.

In Fight Club, Project Mayhem was born from this same discontent—a group of men who found purpose through chaos because the system had failed them. They were told to get jobs, buy furniture, and climb the social ladder. But Tyler Durden knew the truth: “We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

The American Dream is now a subscription service, billed monthly, with no option to cancel.

Project Mayhem to Project 2025

History has a habit of repeating itself, albeit with different costumes. In Fight Club, Project Mayhem was a nihilistic revolution—a fight against a consumerist society that treated people as commodities. It was about tearing down the system, about breaking free from the emasculating grip of retail catalogs and 9-to-5s. In 2025, its echo can be heard in Project 2025, a right-wing think tank initiative aiming to radically restructure the U.S. government. This isn’t the first time disillusionment has sparked revolution, and it won’t be the last.

The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 was born from economic despair, class resentment, and disillusionment with a corrupt ruling class. It was marketed as liberation but delivered authoritarianism. The neoliberal revolution of the 1980s promised prosperity through deregulation and privatization, only to concentrate wealth in the hands of the few. And then there’s fascism—the authoritarian seduction that promised order amidst chaos but delivered iron-fisted control. Like these movements, Project 2025 thrives on the disillusionment of a big chunk of our society who feels left behind, weaponizing resentment and promising a return to greatness that never really existed.

No, they’re not blowing up credit card buildings or fighting in basements, but they are dismantling democratic norms brick by bureaucratic brick, all while wearing suits and patriotic lapel pins. It’s a slow and exhausting insurgency, via attrition. Where Tyler Durden recruited by whispering in the ears of broken men, Project 2025 recruits through ideological indoctrination, flooding the zone with chaos, and viral misinformation campaigns. Both feed on discontent. Both offer an identity to members of society who feel abandoned by the promises of modernity. But Project 2025 does it with a smile, a handshake, and a promise to "make America great again."

The revolution won’t be televised, but it will be live-tweeted. The architects of Project 2025 understand that the battlefield is digital. They’re fighting for influence in newsfeeds, on YouTube channels, and through meme warfare. The anger that drove men to fight in basements now drives them to comment sections, conspiracy forums, and voting booths. And while Tyler Durden blew up buildings to erase debt records, Project 2025 is dismantling public institutions to erase the social safety nets that kept this generation afloat. Different methods. Same chaos.

The Way Out?

Fight Club sold a strong brand of chaos and nihilism. “Maybe self-improvement isn't the answer, maybe self-destruction is the answer.”

Tyler Durden saw destruction as the only way to reclaim humanity. Burn it down. Start over. Reset the clock. But that was fiction. In 2025, chaos isn’t the answer—it’s the status quo. Destruction is easy. Building is hard.

We are weirdly accepting of this today because we’ve gotten lazy. We slap a hashtag on a problem and call it a movement. We turn rage into retweets, activism into aesthetics, and then wonder why nothing changes. Why? Because real change is inconvenient. It’s ugly. It’s expensive. And it means questioning the systems that made us comfortable.

We need to stop pretending that we can consume our way out of cultural decay. No, ‘self-care’ products won’t fix a broken healthcare system. More dating apps won’t cure loneliness. More influencers won’t bring us purpose. We’ve built an entire economy on selling band-aids for bullet wounds, and it’s not working.

Want a way out? Start by ripping off the veneer. Admit that the American Dream may feel to some like a Ponzi scheme and rewrite the rules. Education shouldn’t be a debt sentence. Work shouldn’t mean selling your soul for health insurance. Community shouldn’t be an app feature.

We need to stop screaming at each other and start talking to each other. That may come off as reductive, but it shouldn’t. We need to listen to people we don’t agree with and acknowledging that their anger might be justified—even if their solutions are terrifying.

Or we can keep doing what we’re doing: attacking each other and watching the world burn, while rage-tweeting about the heat. Or, as Tyler would say, “Nothing was solved when the fight was over, but nothing mattered.”

What do you think? Comment, share, agree or disagree!

Sources

https://www.bls.gov/

https://www.brookings.edu/

https://www.federalreserve.gov/

Loneliness and social disconnection among young men: [Bowling Alone, 2000]